Just outside of Los Angeles is a movie set known as Paramount Ranch. The ranch is a well-used filming location; its buildings appear so often in western-themed movies and TV shows their familiarity can become an annoying distraction.

When the set isn’t being used for filming, it’s open to the general public. You can roam the same streets traversed by The Dukes of Hazzard, Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, and the robots of Westworld.

As you wander through the set (it takes about four minutes, if you walk slowly) it becomes obvious that the “buildings” have no solidity; they are mere facades. As one-dimensional as some of the films shot there. (No offense to The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas.)

Paramount Ranch is useful because its facades can be made to simulate any aspect of our shared imagery of the west. These images don’t necessarily represent any actual frontier town; it is their iconic familiarity that makes the fictionalized appear authentically western to us.

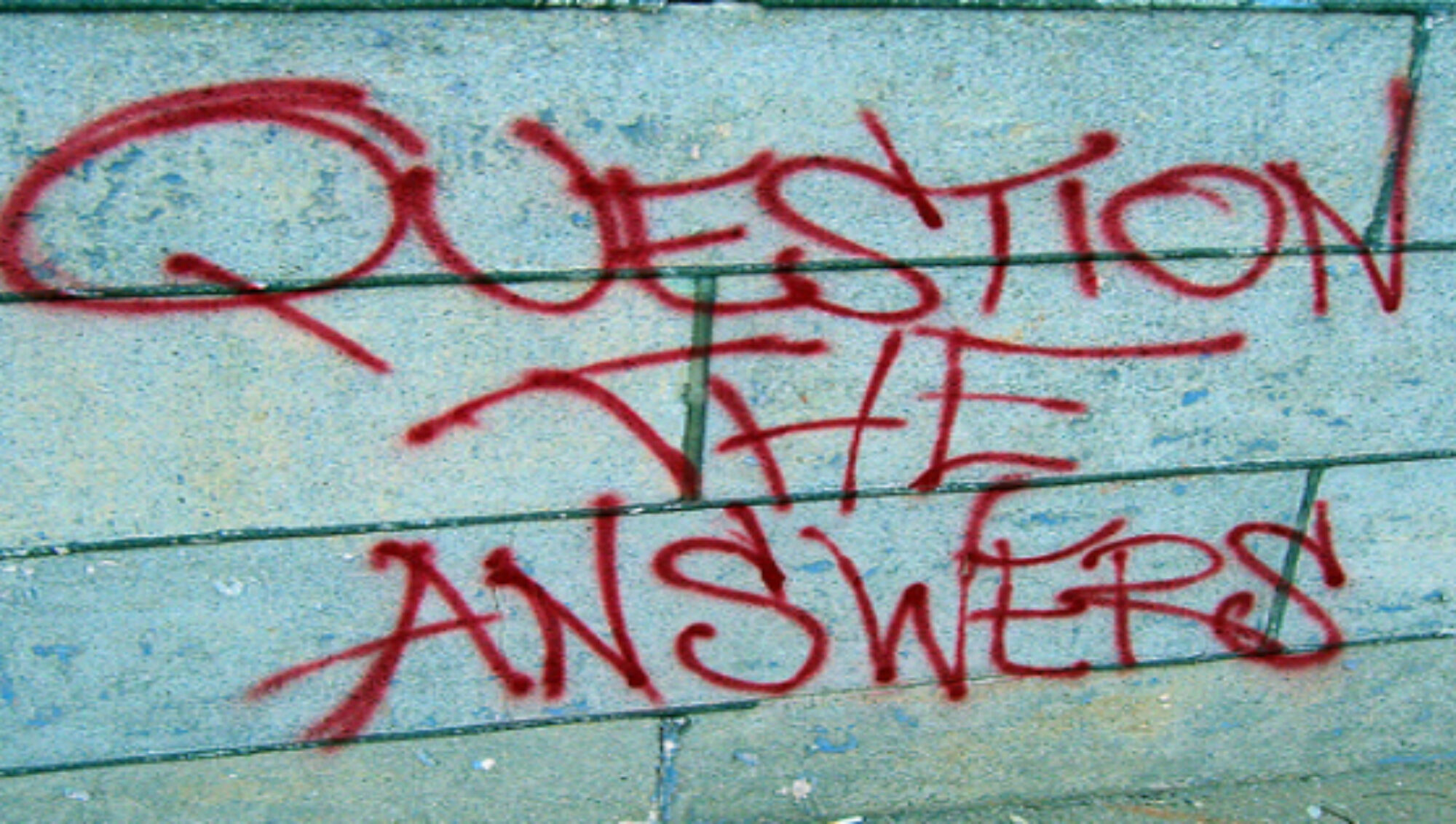

The general sense we have of the underlying simulative aspects of films and advertising can distract us from the pervasiveness of imagery in our own lives. A simulation is a sleight of hand; a misdirection into the realm of imagery and representation. It is a world in which nothing is as it seems.

Simulations hinder our ability to differentiate between truth and reality, allowing the powerful to engage in stagecraft which comforts us, but conceals intentions and objectives. Our current politics has become a realm of symbolism and metaphor with little substance.

Though the political has historically functioned as a territory of sorcery and enchantment, our current vortex of illusion emerged fairly recently. In the 1980 presidential election millions of Americans were convinced that “trickle-down” economics represented a spirit of “free enterprise” which would financially benefit all.

However, the ocean of wealth that flowed to the few drizzled barely a drop down to the many. Those in power realized they could separate the metaphor of “free enterprise” from the actuality of its outcomes, and that even those most harmed would yield to a symbolic American freedom authenticated through economic inequality.

‘Governing today means giving acceptable signs of credibility. It is like advertising and it is the same effect that is achieved – commitment to a scenario.’ Jean Baudrillard

The resultant division between the 1% and everyone else has been maintained not through overt repression but through simulations of openness and inclusion in the political process. The forces of hierarchy persist behind the pageantry of democracy.

Every town hall meeting conducted by a reluctant politician relies on the symbolic. Familiar elements are deployed which, in some way, represent “open discussion” to those attending – a public forum, time for questions, and so forth.

The extent to which a member of Congress actually thinks about what is being said by their constituents is dubious at best. Politicians at these meetings often have the pained expression of someone who’s been given number 88 at the DMV and just heard the loudspeaker announce “3.”

It doesn’t matter. Politicians and constituents aren’t engaged in deliberation; they’re performing a ritual. Everyone plays their role. Those in attendance dutifully ask specific questions and politicians flee along a circuitous route avoiding any meaningful responses. The process repeats: pointed question followed by rhetorical sidestep. This is the familiar script. Constituents leave the meetings believing they’ve engaged in deliberation, but they were really part of a theater-in-the-round production touring the country.

Town hall meetings are simulations; they are phantoms of an ideal of civic engagement that exists only in the symbolic. The meetings are artful veneers; the familiarity of their iconography provides the illusion of speaking to power. The ritual replaces the real.

Presidential debates are the pinnacle of contrivance. As in town hall meetings, the theatrical overwhelms the substantive.

Watching debates, we are seduced by the ceremonial. Candidates hover behind phallic lecterns of power; journalists sit passively at tables earnestly lobbing questions which inevitably disappear into labyrinths of pointless phrases and hollow rhetoric. Myriad rules on speaking time and the structure of responses fabricate a phantasm of substance. As we watch the debates, we are aware of the emptiness of the liturgy but remain captivated by its incantations.

In the 2016 presidential debates we were absorbed into a clash of the unreal. One candidate was so formularized everything she did seemed like an ironic parody of how a simulated politician acts. She lost to the hate-child of George Wallace and Huey Long – a tiny-handed flimflam who brayed the familiar libretto of the demagogue. Our “democratic election” was a contest between wizards of Oz; two illusory floating heads distracting us from the void behind the curtain.

Donald Trump is the most virulent political creature to emerge from our Orwellian lagoon. He has embraced politics as art(ifice). Democracy becomes a musical where the plot and dialogue don’t matter as long as the songs are catchy.

Trump is angered when people refuse to hum his incendiary tunes and instead focus on the actual lyrics. For the president, the meeting in Helsinki with Putin was a dazzling success; it may have been a political disaster but it had all the markings of a Tony award winning production.

Trump believes that, in politics, the spectacle is sufficient. He may be right.

Simulations maintain inequality by mollifying the public. We willingly acquiesce to a democracy in which inequality is fueled by a symbolic freedom and perpetuated through the pageantry of participation. But we are not merely spectators, we are also the actors. We have the potential to end these simulations by refusing to participate in them.

The powerful maintain their position by turning all the world into a stage. We can no longer be merely players.

–RWG–