I believe Donald Trump’s policies are evil. I also believe the person who selfishly won’t let me into their lane on the freeway is evil. Both of these are what I would call “disfavored actions.” But what is it that propels the first belief into a national discussion on the nature of immorality and the latter into unsolicited referrals for counseling?

If we consider locking children in cages to be evil, what do we say about the killing of six-million Jews? Is it possible for evil actions to be ranked comparatively? Is Hitler “more” evil than Trump? If so, by what standard?

How do we decide which actions are “wrong” – selfishness, lacking empathy, etc. – but not necessarily “evil.” The freeway driver may embody these negative qualities, but we wouldn’t say they rise to the level of immorality. What is the calibration – the measurement – that forms the line of demarcation?

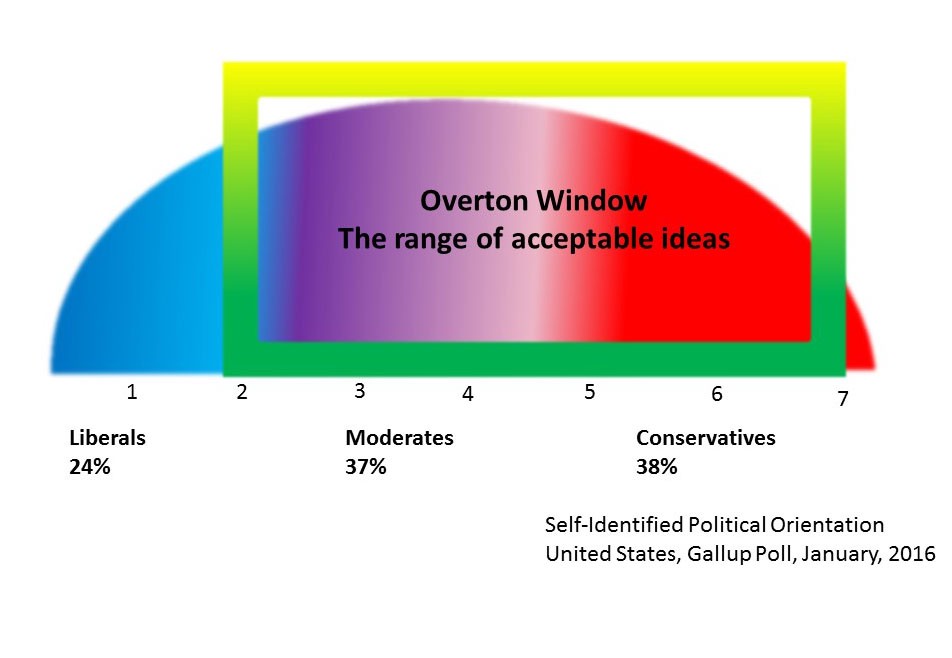

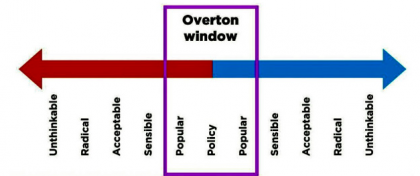

For large swaths of social media, there seems to be little question as to whether Donald Trump’s policies reach a level they denote as “evil.” This certainty usually emerges from a calculus which evaluates Trump’s specific actions against an abstract set of “moral principles” – equality, liberty, justice – which have no definitive meanings.

But “evil” is not a compilation of policies, measured and compared to politically malleable tenets of “natural law.” Evil is a strategy; it is the refusal to acknowledge the worth of others and to exclude them from the processes which determine the quality of their lives. Evil is not a hierarchy of disfavored actions; it is, at its core, the insidious belief that there are differences in human value. Evil seeks not only to divide, but to erase.

This strategy infuses all levels of our social, economic and political lives. It is a Hydra; the face it displays – the policies it produces – depends on the context in which it functions. Evil is a highly adaptable shape-shifter on a constant search for unguarded spaces and unseen opportunities.

The killing of six million Jews and locking children in cages are based on the same strategy; the erasure of the “other.” One action is no more or less evil than the other; in each case, the strategies of evil expanded into the social and political spaces allowed to it.

The Trumpian erasure occurs on many levels. In its most overt form, erasure shapes Trump’s views on immigration in which non-whites are rendered invisible by imperious exclusion and contemptuous rhetoric. The Trumpian constructions are not merely hierarchical; they generate a distinct dichotomy of human value.

The Republican agenda is premised on the delusion that there are two different kinds of people; the very wealthy and everyone else. This economic division becomes the marker for differences in intrinsic worth. The non-super wealthy, comprising over 99% of the population, are considered to be less fully human than the very well-off. Respect and dignity are based on a sliding scale of net-worth.

In the Right’s strategies of erasure, one group – extremely wealthy, white, heterosexual males – dwell on a higher plane of existence; while all others – the poor, people of color, the LGBT community, anyone immigrating from a non-Nordic country – tumble into an abyss of nothingness. Unrecognized and unacknowledged, with a potentially dwindling ability to participate in processes of self-determination.

Within the strategies of erasure which constitute evil, individuals with power validate their own sense of intrinsic worth; not merely through hierarchy but through the forced non-existence of others. That is why these strategies are so prevalent and so difficult to dislodge.

Strategies of erasure are not eliminated from our lives by outlawing specific actions and relations. But rules and regulations do provide barriers against these strategies; they ultimately construct the maze through which evil slithers. Change the laws on sexual harassment – alter the walls of the maze – and the strategies of erasure will quickly adapt, finding new unguarded venues and targets. The more de jure rules deflect it, the more de facto openings it will seek.

It can be comforting to point at Donald Trump and scream “EVIL!” In the cathartic moment, immorality is contained within a singular orange-tinted vessel; the product of a particular warped psyche.

But even the most egregious displays of evil shouldn’t blind us to the strategies of erasure which course through our social fabric. We must continuously churn the soil of social and economic relations, rooting out those strategies wherever they occur. Trump may be the not-so-bright light of erasure, but his glare should not obscure the micro-fissures of indignity which twist through so many of our lives.

–RWG–