Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com

THEORY IN ACTION

Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com

The U.S. court system is government funded. Each citizen, whether or not they are ever party to a judicial proceeding, contributes to the financial sustenance of the system. Through constitutional interpretations, every citizen is entitled to a basic level of legal representation in all criminal cases, free of charge.

These are very much the same principles embodied in most proposals for Universal Health Care. Yet it is only Universal Health Care which is framed in our politics as a kind of Trotskyite Trojan Horse intent on destroying the moral fibers of the American social fabric.

Why is Universal Health Care constructed as the spearpoint of a leftist insurgency, while the court system, for all its problems, has not been the focus of a similar “let corporations run everything” approach? Why haven’t Democratic and Republican politicians banded together to decry our court system as a Socialist menace and extolled the virtues of efficiency and innovation that would emerge from a corporate-run system of justice? Just as they’ve done with Universal Health Care.

Why aren’t there insurrectionists draped in Trump flags and moose antlers storming the Supreme Court demanding that the courts be run by Anheuser-Busch? (“One sip of our new limeade cooler and you’ll yearn for the death penalty.”)

The political differences between the court and health care systems are not based on substance; they’re strategic. The Constitutional creation of our court system, unlike the current proposals for Universal Health Care, was not whipsawed through, and torn apart, by the contemporary political fun-house of meaningless labels and empty categories.

When the Founding Fathers constructed this country, the role of the courts, and the crucial importance of a fair and impartial system of justice, was foremost in their minds. The interference of the British government in the workings of colonial juries was a strong impetus for the American Revolution.

However, despite evidence of the British government’s malfeasance in colonial courts, the colonists didn’t turn away from a government-established court system. Instead, they gave Congress the power in Article III of the Constitution to establish the Supreme Court and any lower federal courts deemed necessary. The founding fathers were drawn from the wealthiest class in America, yet they didn’t construct the federal courts as a profit-making enterprise.

A government-run hierarchy of courts was put into place because it represented the most rational, reasonable way to develop an impartial judicial system; amplified by the Constitutional protections afforded by the Bill of Rights to those accused of crimes.

The greater fairness of a government-run, rather than private-enterprise maintained, court system seems clear. If someone you know is falsely accused of a crime and their attorney indicates they need three days to present an adequate defense, you don’t want the judge responding “Sorry, Pepsi only allows for one-day trials.” The Miranda Warning stating “if you cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for you” is not followed by an asterisk declaring “your lawyer is only free after you pay for the first 4 hours of their time and twenty-minutes of every hour thereafter.”

As a nation, we don’t want profit-making entities such as Pepsi structuring our courts system and dictating whether or not we will be physically free. Yet, this is exactly what we do in terms of our health care system where our physical well-being and very existence is at stake.

All developed nations other than the U.S. have some form of Universal Health Care. This unanimity isn’t the effect of ideological trench warfare but, rather, a recognition across the political spectrum that government-run insurance is the most efficient means of providing health care.

But American politics is not about efficiency because it isn’t based on substance – the pre-requisite for any reasoned debate. Instead, every proposal, every program, is dragged through the chopper-blade of contemporary politics in which it is given a label and then twisted and contorted to fit into a constructed political category.

In our politics, terms such as “left,” “right,” “center,” “Socialist,” “liberal” are fervently embraced by adherents and hurled as invectives against opponents. But even as the labels fly across social media they have been emptied of any substance. They are strategic placeholders, pointing to nothing other than a vague emotional attraction to the words themselves.

The labels and categories are not based on reason or rationality and shouldn’t be engaged as though they are. They are like paintings in a museum; we are aesthetically attracted to some labels and not to others. If someone invokes a label as though it has some real meaning – “I could never support Universal Health Care. It’s too leftist and Socialist for this country” the response should be ”I like Starry Night. It’s very blue.”

We are like the prisoners in Plato’s Cave; unknowingly chained to the ground, staring at, and arguing over, the shadows on a wall. We fight over terms and labels which are meaningless. Behind us, are the politicians, projecting the shadows, diverting our attention with hollowed-out ideological categories and a vacuous topography of left, right, and center.

In Plato’s allegory of the cave, one of the prisoner’s breaks free and ultimately leaves the cave and the world of shadows. But most stay; the shadows are comforting and familiar. Presumably, they continue to argue and wage political warfare over nothing until the cave is completely enveloped in flames.

–RWG–

Image: William Brown / Op-Art

Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com

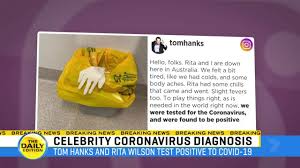

Let me be clear at the outset – I am in no way calling for, longing for, instigating for, or in any way recommending, the death of Tom Hanks. How could anyone wish that on Hanks? He is a beloved figure in this country. He is our everyman, transcending social and political differences. And it is precisely this distillation of America diversity into the singularity of one individual which underlies the question posed in the title of this essay.

Would the death of Tom Hanks from Covid-19 have forged a single iconic moment, overwhelming both the complexity of medical evidence and the sharp-edged blades of American politics?

Throughout the history of this country, arguments calling for Americans to change the way they interact with the world have been subsumed by the habitual forms of everyday life. A rousing of the nation from the slumber of the customary has rarely been generated by appeals to rationality or philosophy. Action is generated by emotion not reason.

In the 1980s, the onset of AIDS seemed, like the coronavirus, to be a distant and foreign enemy. AIDS was viewed as an obscure disease that only attacked populations already cleaved from the norms of American society. It was that disease killing those people.

The death of the actor Rock Hudson in 1985 profoundly altered the nation’s view of the AIDS epidemic. Hudson projected the kind of warm, self-effacing jocularity that is now bestowed upon Hanks. To many, Hudson wasn’t one of “them,” he was one of “us.”. If he could be struck down by the disease, so could anyone.

In the early days of Covid-19 – meaning a few short weeks ago – the virus was portrayed as having the same quality of otherness as had AIDS. The Trump administrant attempted to construct a narrative in which the disease was only spreading in other countries, carried to our shores by “foreigners” who could be quickly separated and isolated.

When the virus first manifested itself in America, it was conceptually framed as being limited to particular sub-groups such as “those people” on cruise ships who “really should have known better.” If you were willing to avoid boarding a large boat serving questionable shrimp, you were safe.

Though the voices decrying this narrative were numerous and varied, to many the medical arguments seemed complex and arcane. Just as in the early months of the AIDS epidemic, the coronavirus was something that happened to “other people.”

The subsequent change in the attitude of Americans came not from sifting through the medical evidence, but from the sheer quantity of people being infected and killed. Absent a single, galvanizing “Rock Hudson” moment, the disease had to begin its rampage through cities and communities before Americans acceded to the reality of “hey, this could happen to me.”

Hanks was one of the first nationally known celebrities to be diagnosed with Covid-19. His diagnosis seemed for a moment like a clarion call to action, but his recovery may have furthered a framing of the disease as being far more innocuous than it is.

The impetus for national change often requires the transmutation of an individual’s anguish into the realm of the symbolic. In the case of Hudson, the “everyman” had to die in order to arouse the public to its own vulnerability.

A long happy life to Tom Hanks. And to a world which doesn’t require any individual to be transformed into an icon of suffering for the country to find its own moment of transcendence.

–RWG–

Richard W Goldin, Lecturer in Political Science, California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com