There was a time, when the world was younger, that I believed there was a kind of justice in the universe by which good people would be rewarded for their goodness and bad people would be punished.

The methods and means by which this universal justice would be implemented was always a bit unclear in my thoughts, though I think there was some element of material rewards or deprivation. My belief system wasn’t robust with specifics; it was grounded more in a hazy hope that those people who consistently treat others badly would ultimately be faced with some dimension of universal balance. It was an ambiguous yearning that the people who regard others as a shared humanity would ultimately live the better lives, while the narcissistic egoists – or, to use a term as evocative as it is crude, the “dicks” of the world – would be faced with material failure.

Dickishness is the purgatory that lies between decency and evil. Though it usually doesn’t by itself reach the level of evil, it can often serve as its ground. Context is important; the dickishness love of hierarchy can easily mutate from mere vanity and disdain to far more insidious applications. Though we may encounter the truly evil at few points in our lives, dickishness is often the daily environment in which so many are forced to live.

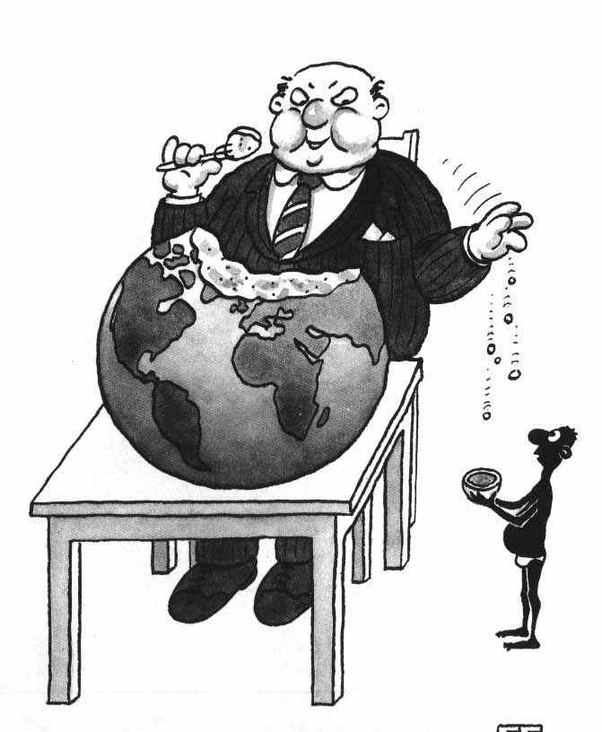

Many of us are frequently compelled to consume a smorgasbord of other peoples’ dickishness. We are fed a massive salad of “I’m better than you” topped with an “and I’ll treat you with contemptuous arrogance to prove it” dressing, followed by a heaping mound of self-importance with an oozing side of condescension. All of this is served to us on a grotesquely huge platter of insecurity, ego, and rationalization.

Dickishness can often be found in politics, but it isn’t based on particular political philosophies or policies. It crosses the aisle entwining itself into all facets of political life. It’s Donald Trump mocking the disabled and Amy Klobucher tossing binders at her staff’s heads. It’s the smugness and pomposity that power breeds.

Dickishness is the assertion of a delusional superiority which often seeps from institutional hierarchies into valuations of human worth. In my own situation – a university adjunct for almost two decades – I have been forced to deal with tenured professors, many of whom attempt to cling to an imagined slightly higher rung on the academic ladder by demeaning adjuncts and the work we do.

Assistant Professors, become Associate Professors, become Full Professors, each move bringing with it increased material benefits. Adjuncts stay as adjuncts, contingent and vastly underpaid – mere cogs in the machine. Tenured professors often regard this inequality with either a condescending indifference or as a useful symbol of their own supposed grandeur, while at the same time they populate CNN and MSNBC weeping for the downtrodden.

While this particular hypocritical form of dickishness is rife amongst the tenured, dickishness is certainly not limited to the sanctimony of academia. If you met someone who proclaimed that their boss was a giving, humane person who always treated everyone with exactly the same amount of respect they want in return, you might be inclined to ask, “Is your boss a unicorn?”

Having witnessed the resplendence of dickishness that is academia, I came to realize that there is no universal disseminator of justice which rebukes the narcissistic and ultimately rewards those that treat others with respect. Perhaps it is dickishness which allows one to rise to the top of a hierarchy; perhaps it is the ascension itself which transforms one into dickishness. Either way, the dicks will win and the winners will be dicks. Even having attained a Ph.D., this is probably the most important lesson I’ve learned from the university.

In the end, I can’t help but occasionally glance nostalgically over my shoulder at what I once thought. The belief in some kind of just order may have been misplaced, but there was comfort in being naive. But I have come to realize that there is no universal arbiter against dickishness; we can only as individuals commit ourselves to never becoming what we abhor. To refuse to do onto others as has been done onto us. The material rewards of dickishness can be many, but they are always an insufficient compensation for our humanity.

—RWG—

Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com