The waves of gentrification which have flooded much of Los Angeles have reached the shores of Boyle Heights; a historically lower income, now mostly Latino, neighborhood located across the L.A. River from downtown. The economic forces enveloping Boyle Heights are typical of the contemporary transformation of urban centers into Roman Coliseums in which the underprivileged are pitted against the lions of capital.

Many long-time residents of Boyle Heights are attempting to resist the forces of their own extinction. Entering the fray, ostensibly on behalf of the community, is a traveling troupe of self-proclaimed political-aesthetic quasi-Marxist pioneers known as Ultra-red.

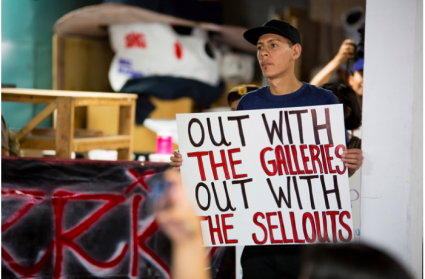

One of the effects of the Ultra-red invasion, has been a heightened focus on the economic impact on Boyle Heights of a few art galleries; many, but not all, of which have recently appeared in the neighborhood. Even those galleries located in an underused industrial area have become the target of the resistance.

Through the intervention of Ultra-red, and its affiliate groups, many of the residents of Boyle Heights have come to view the galleries as the generators of gentrification. They believe that closing the art galleries will substantially alter, if not halt, the economic forces headed in their direction. This claim has left most gallery owners in a state of confusion; they argue that the vitriol against the galleries does not take into account the complex forces of gentrification and misunderstands the galleries’ actual impact.

Their bewilderment is understandable. Art galleries do not simply materialize from another dimension dragging the unwilling forces of gentrification behind them. The galleries are the initial surge of an economic tsunami – a position that has been occupied in other communities by coffee shops, restaurants, retail stores, etc. Though the galleries are being presented as the harbingers of economic disaster, the fervor against them is disconnected from their actual impact on gentrification.

The art galleries have become a primary target of political resistance primarily because they function as effective points of engagement for the “sonic strategists” of Ultra-red. The economics of the galleries disappear into an intense aura of theoretical navel-gazing about the role of “the artist.” For the residents of Boyle Heights, the art galleries are perceived as an economic force; for Ultra-red, they open-up a series of ruminations on the meaning of “art.”

Ultra-red co-founder Dont Rhine has said “we love…this [Marxist philosopher] Althusser thing [that] ideas exist only in their practice. …[T]hen we can think about, what’s the relationship between the developer who says, no, we’re gonna give you better housing by displacing all of you? [sentence in original]. That’s the practice, not the better housing, the practice is the displacement.”

“Then we can think about” is not a politics; it in no way escapes the gravitational pull of the theoretical. Ultra-red isn’t about politics. It isn’t about theorizing about politics. It’s about theorizing about theorizing about politics.

James P. Carse has written of the distinctions between what he called finite and infinite games. The gentrification of Boyle Heights is a finite game – there are distinct winners and losers in the battle for economic resources. The world of Ultra-red is an infinite game. No matter what happens to the people of Boyle Heights, the game of academia and art will continue. Different from the finite, the infinite game has its own structure of incentives and motivations. Even if the residents of Boyle Heights are cast to the winds, for Ultra-Red there will always be more sound pieces to perform, articles to write, conferences to attend, academic positions to be attained.

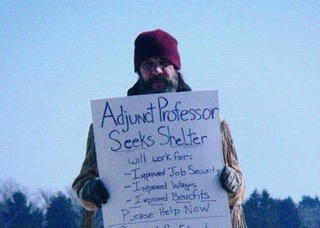

Academic faculties are divided into two very separate classes – well-paid tenured professors and lowly-paid adjuncts. The latter are almost always trapped in part-time positions and virtually never attain a living wage. In order to secure their positions, and their privilege, the class of professors use their power to further marginalize the adjuncts in their own departments. Even those professors who adore spouting Marxist rhetoric say nothing about the inequality they maintain and further.

Rhine has skipped between academic positions, including the University of Chicago and, now, the Vermont College of Fine Arts. In the desire for academic recognition, Ultra-red has sacrificed credibility in order to prosper within a system of oppression. They have joined with – they have become – the perpetrators of an academic hierarchy which damages the lives of so many. The repetition of Marxist jargon cannot disguise their complicity in the further degradation of those who are most in need of political support.

In the infinite game, the material collapses into the conceptual. One can observe this when visiting contemporary art museums or galleries. Upon first encountering an object – a painting, sculpture, or a rambling assemblage of discordant sounds – one is often struck by the total absence of any significance or discernible substance. But fear not – this art has “meaning.” How will you know? Just walk over to a nearby wall and you will discover a posted 3×5 card offering a funhouse jangle of postmodern rhetoric. The accolades of the art world accrue to those who are best at offering a “politics” which, ultimately, points to nothing other than the supposed immateriality of the concept.

Ultra-red spices their jangle of “art” with a litany of Marxist tropes. In so doing, they empty Boyle Heights, and its residents, of any material existence. Positioning the art galleries as the causal factors of gentrification is not intended to alter economic reality. The galleries function as venues for Ultra-red’s political-aesthetic; conceptual theater disguised as politics.

To whom is Ultra-red addressing their “politics-aesthetic politics”? It’s difficult to imagine that people living on the precipice of survival have the time to contemplate Althusser, not to mention placing him within the long lineage of Marxist theory. Apparently, if the residents of Boyle Heights truly want to understand their own situation and save their homes, they have a long reading list ahead of them.

Or perhaps the residents can take a drive to the Otis College of Art and Design where Ultra-red is currently presenting Los Angeles Library for Anti-Gentrification (2012-2017) which is part of an exhibition entitled “Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas (affiliated with the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative, “LA/LA”).

The installation presents the elements of political information – pamphlets and videos about gentrification. “Non-artists” might use these kinds of materials to educate residents about the need for, and possible forms of, resistance. But locating the presentation within the museum’s wall removes the materials from any political utility for the community. The presentation is merely a rumination on what it might mean for an “artist” to proffer political information. No actual facts or knowledge are being conveyed to the people of Boyle Heights.

‘The problem Ultra-red have is a marked failure to communicate, which for a group made up of would-be radical pedagogues is a cataclysmic lapse.’

-Tony Herrington (TheWire)

Ultra-red attempts to position itself as the cutting edge of some sort of political/artistic vanguard movement. But the necessary negotiation between the political and the conceptual is ill-defined and under theorized. Rhine has noted that the relation between art and its political effects “has been a constant problem for us….and maybe…I should just let it go…or maybe the tension is the thing that’s the most productive.”

A group which views itself as the purveyors of a political-aesthetic, should have a much deeper understanding of the real-world politics through which the two realms connect and interpenetrate. The absence of this plagues Ultra-red. Their politics has an “emperor’s new clothes” quality to it – keep tossing conceptual balls in the air and hope that no one questions their political relevance or realizes that they are really meaningless puffs of smoke.

The abstract, conceptual world of Ultra-red ultimately caters to, and is rewarded by, a small privileged intellectual class that is rarely materially affected by that which it ponders from afar. The intrusion of this world into Boyle Heights draws attention and resources away from the complex forces of gentrification, and offers residents little in the way of tools for surviving the oncoming flood.

‘The struggle of the Boyle Heights residents and their protest is material and concrete; it cannot be properly debated with art-writerly metaphors.’

–Dr. Nizan Shaked, Professor – California State University, Long Beach

The fight for Boyle Heights and its residents requires on-the-ground organizing – it requires “getting your hands dirty.” But the “dirty hands” of organizing won’t get you a show at the Whitney Museum. Ultra-red’s hands are very clean. Their “organizing” is a rhetorical gesture; its practices align with the incentives of academia and art, not the community.

‘Ultra-red have retreated so far into the ghetto of critical theory their activities have become irrelevant to anyone living and working beyond the walls of academia.’

-Tony Herrington

To some in Boyle Heights, Ultra-red has been swinging its quasi-Marxist scythe indiscriminately against the art galleries, lumping together recent arrivals with the long-standing community-based Self Help Graphics & Art. The distinctions between these different arts venues requires an understanding of the specific history and politics of Boyle Heights. However, Ultra-red doesn’t merely ignore the specificities of the material world – it attempts to erase them.

Within the realms of academia and art, Ultra-red’s reputation rests on nothing other than its own narrative. The immateriality of its politics has required two survivalist responses. The first is rhetoric sufficiently esoteric to veil its own emptiness. Second, Ultra-red doesn’t merely reject the material in its “politics.” It attempts to root out and destroy those who join the aesthetic and the material in ways that challenge the universality of their narrative. In their struggle for institutional supremacy, Ultra-red is not merely irrelevant to the people of Boyle Heights – they are a danger to the future of the community.

Ultra-red was founded in the 1990s by Marco Larsen and Dont Rhine. After a few years, the group, in Larsen’s view, moved away from its original purpose of affecting political change through the sound recordings of specific communities and actions. When Ultra-red intervened in the demolition of the Pico-Aliso housing projects, Larsen witnessed the group’s loss of materiality, and the abjuration of politics in favor of an ineffective obscure, self-absorbed “artism” that was of no benefit to anyone other than burnishing the institutional reputation of the group’s leader. (Which has actually worked very well for Rhine. After all, you don’t get to be a faculty co-chair at the Vermont College of Fine Arts by actually helping people.)

Larsen believed that Ultra-red’s purpose was to utilize the words and sounds of underrepresented people in order to give them the voice they so sorely lacked. The harshness of the displacement of Pico Aliso’s residents compelled Larsen to work hand-in-hand with those effected. For his part, Rhine began distorting the recorded voices of the people – furthering their invisibility – and using their pain as fodder for musical compositions.

The wave of Ultra-red’s immateriality – and its disregard for the lives of those it claimed to represent – had subsumed the people themselves, transforming their voices into unrecognizable sounds. Larsen believed that sound art should illuminate the lives of the community, not obliterate them on the altar of self-indulgence.

Rhine’s reaction to Larsen’s quitting did not provoke the kind of thought and self-reflection needed by Ultra-red concerning the connection between its “art” and its “politics.” Perhaps this is why the connection is such a “constant problem.” Rather than listening to Larsen, Rhine ignored the one person who was viewing sound projects from the side of the community. Rhine’s reaction was to expunge all mention of Larsen from the group he had helped found. Larsen became a ghost – his name was removed from Ultra-red’s history, as was any thoughtful dialogue on the group’s “politics.”

Not content with Larsen’s “disappearance” within the group, Rhine went further. According to Larsen, Rhine spread false rumors about his moral character in an attempt to diminish his reputation in the Los Angeles art community. Larsen had questioned the politics of Ultra-red; the response was to eradicate him and the threat he posed within the art community to the group’s political authenticity. Larsen had pointedly declared that the emperor had no clothes – the reaction was to shoot the messenger.

Rather than encounter the “other,” Rhine chose to expel it. If Larsen had stayed, Ultra-red might be a far more relevant synthesis of art and politics. But the group of self-proclaimed Marxist artists was unable to apply the Marxist dialectic to their own situation. Then again, Ultra-red isn’t really Marxist – it’s more of a Lenin/Stalin soufflé. It combines the self-involvement of a Leninist vanguard with the paranoia of a Stalinist purge.

Ultra-red is now repeating this history in Boyle Heights as it attempts to undermine Self Help Graphics & Art. SHG “inspires the creation and promotion of new works by chicano and latino artists through experimental and innovative printmaking techniques and other visual art forms/ media. Since 1973, SHG has been the intersection where arts and community meet, providing a forum for local and international artists.”

For decades, SHG has placed itself directly in the intersection that Ultra-red is unwilling to acknowledge. SHG’s focus on the role of art in the betterment of the community reveals the social and material emptiness of Ultra-red’s political-aesthetic. The emperor still has no clothes.

SHG’s material-based synthesis of art and politics represents a threat to Ultra-red’s academic narrative and must be defamed and expunged. Materially, a community-based organization such as SHG is not the same as the recently-arrived art galleries. Focusing on the galleries, and viewing all art venues as the same, does nothing in terms of hindering gentrification or helping the community. But it is an important component of protecting and burnishing Ultra-red’s narrative and reputation.

Elizabeth Blaney of Ultra-red claims that all those targeted by Defend Boyle Heights (which protests against art galleries, including SHG) are gentrifiers or enablers. Joel Garcia, Director of Programs at SHG, denies this, responding: “our existence here threatens [Ultra-red’s] validity to being social practice artists. We embody community arts practice. These artists are trying to usurp that. Attacking Self Help Graphics legitimates them – it has everything to do with their professional positioning.” Garcia’s comments, and work, are far more perceptive about the complex relations between art and politics than anything emanating from Ultra-red. Perhaps he should be the faculty co-chair of the Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Ultra-red believes they are outside the economic and political processes they observe. They don’t seem to comprehend the effects of their actions on furthering the forces of gentrification they decry. As the deluge comes, some in the Boyle Heights community are trying to construct rafts and find higher ground for those precariously positioned. Ultra-red is playing a different game. They are not invested in the outcomes of Boyle Heights; if the worlds of art and academia remain entranced by the vapidity of their politics, their game continues. But treating poor peoples’ lives as a conceptual apparatus attune to the machinery of art and academia is not only ineffective, it’s disturbing.

–RWG–