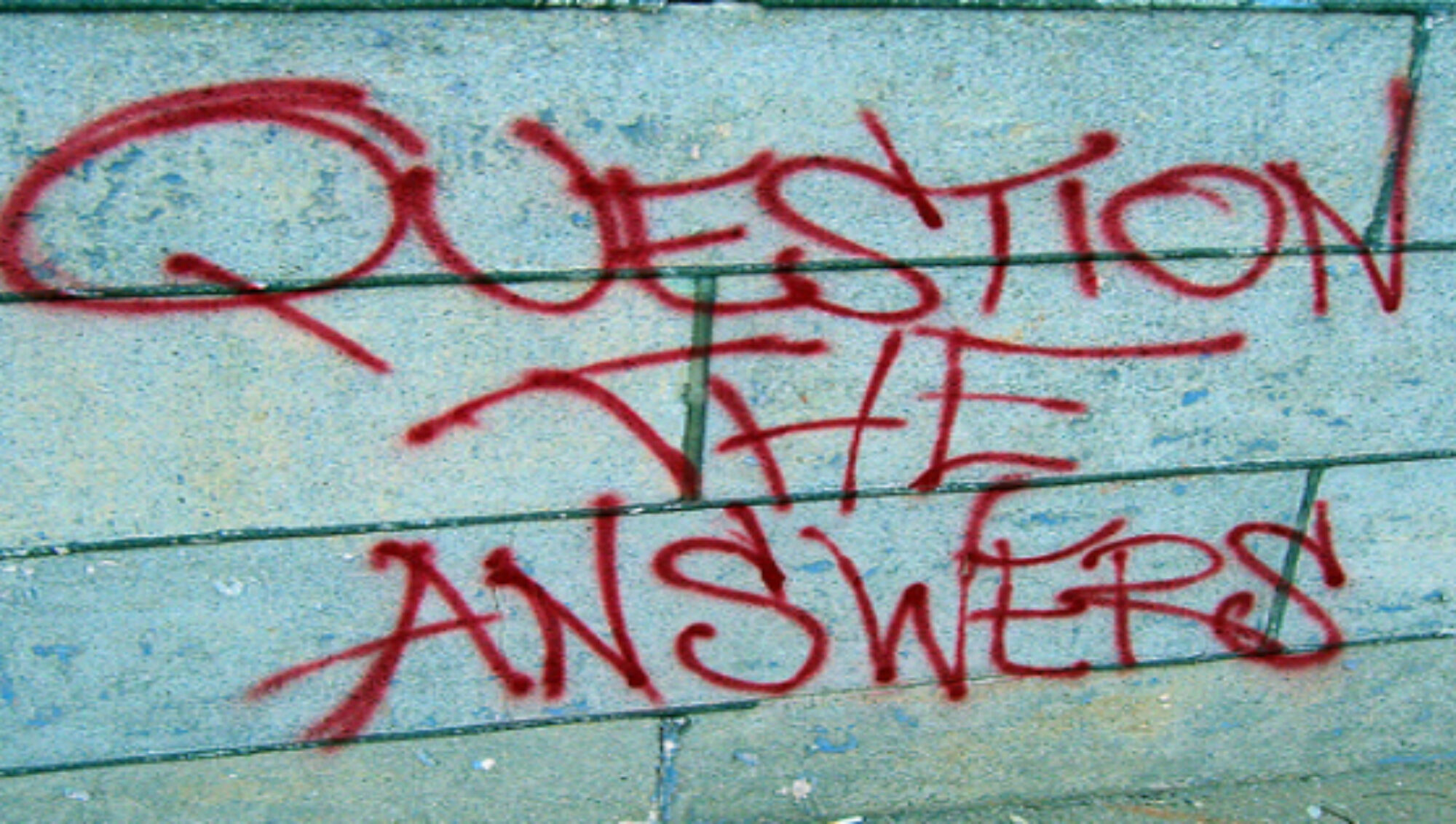

“Quit lit” is clearly a rising and resurgent cultural phenomena. After all, it’s been given the kind of catchy, rhyme-y name you’d force on a pet ferret. But behind the roll-off-the-tongue moniker, the artifacts of quit lit – social-media essays, written primarily by former university adjuncts, detailing their disillusionment with academia and reasons for leaving the profession – are a flare in the darkening sky, illuminating an America in which, more than ever, winning is everything.

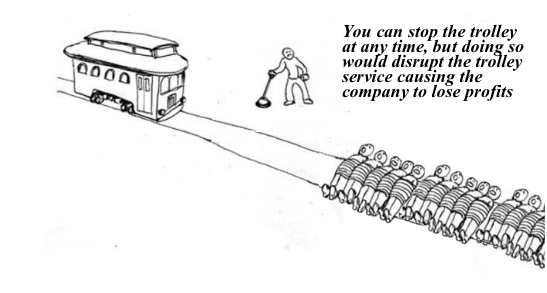

Those, like myself, who first entered academia expecting an open-ended pursuit of scholarly wisdom, now find themselves trapped on a runaway train which long ago flew off the rails of intellectual engagement. Universities claim they are guiding students on a pilgrimage to enlightenment while administrations reshape faculties into neo-liberal class stratifications and tenured professors disparage teaching in order to win the status game over adjuncts.

A useful perspective for framing the descent of academia, and situating it within the broader disjuncture between expectation and reality which has come to shape much our lives, is James P. Carse’s Finite and Infinite Games. According to Carse:

“A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

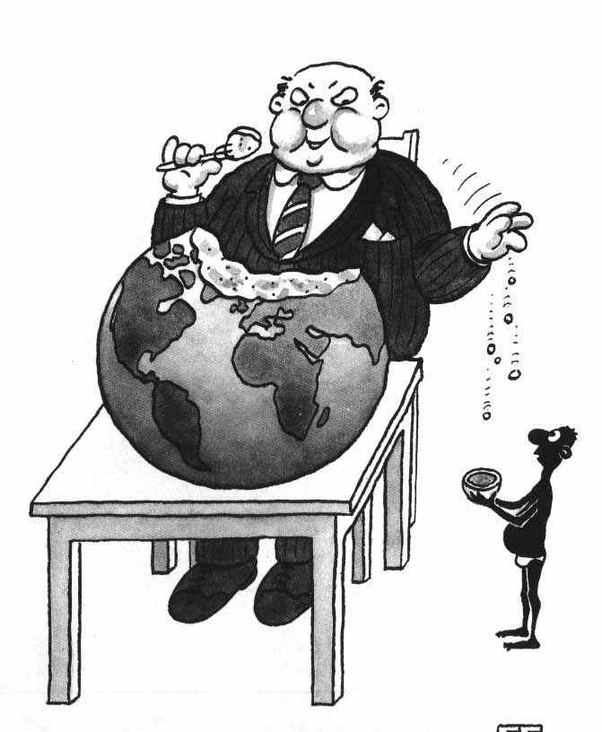

The construction, maintenance and expansion of national parks is an infinite game; gashing the land for the financial interests of a dying oil industry is finite. A politics devoted to the “arc of justice” is infinite; a system of justice contorted by wealth and power is finite. In academia, the collaboration of administrators, tenured professors and adjuncts on the search for, and transmission of, new vectors of knowledge is infinite; an administration pre-occupied with reshaping universities into profit-making machines and a professorial class fueled by egoism are decidedly finite.

As the nation’s passage towards social and economic equality plummets into the finite, academia needs to be the guardian of the infinite game. Its refusal to do so, and its obsession with profit, prestige and reputation, isn’t only a failure of universities; it threatens the entire narrative of progress upon which this country was founded.

The intellectual promise of history was marked by a move from the finite to the infinite. The tide of the Enlightenment erased the absolute truths of the Classical and Medieval ages, substituting instead a faith in open-ended processes of reason and rationality. The eternal unchanging essences of Plato’s Forms were replaced by the “I think therefore I am” of Descartes. Progress manifested itself in a continuous quest towards elusive horizons of knowledge.

We are now witnessing this historical process in reverse. The infinite game of progress is increasingly bruised and battered by a nation which has become a never-ending rugby scrum.

Academia used to be the protector of the infinite by opposing attempts to shape all of society around the finite goals of the economic sphere. But universities now function as large corporations and worship at the same alter as all financial institutions.

The increasing budgetary reliance of universities on part-time, contingent, underpaid adjunct/teachers has been twisted into a new finite game. Adjuncts, and teaching, now function as the maligned “others” whose lowered status secures the ongoing “victory” for well-paid, status-driven tenured professor/researchers.

“[In the finite game] it may appear that the prizes for winning are indispensable, that without them life is meaningless, perhaps even impossible.”

Publications have become the singular path to the financial security of a tenure-track position. The strategic focus on stockpiling publications has deformed the vectors of academic research, and the odyssey of knowledge, from infinite to finite. A study at UCLA found that, in the sciences, “researchers who confine their work to answering established questions are more likely to have the results published, which is a key to career advancement in academia. Conversely, researchers who ask more original questions and seek to form new links in the web of knowledge are more likely to stumble on the road to publications, which can make them appear unproductive to their colleagues.”

Participation in the game of academia is limited to those who have willingly, even eagerly, jumped into the finite. The rewards of tenure-track jobs flow to those who abjure long-term open-ended scholarly pursuits in order to excel in the sport of publication accumulation.

“Since finite games are played to be won, players make every move in a game in order to win it. Whatever is not done in the interesting of winning is not part of the game.”

The academic competition is ultimately won by those who can construct the highest heap of articles and books. Embracing the quantification of academia has become a useful, though highly simplistic, tool for an enterprise increasingly devoted to separating out winners (professors) from losers (adjuncts).

“A title is the acknowledgement of others that one has been the winner of a particular game”

Publications are primarily strategic; they are designed not to share knowledge (though that might be an unintended consequence) but to win the game. Thus, the forces of aggregation are in no way deterred by the reality that at least one-third of all social science articles, and 80% of those in the humanities, are never cited.

Adjuncts of my generation offer a unique viewpoint on the relation between the finite and the infinite. We entered an academia which was seemingly still engaged in the infinite game, only to witness its swoon into the finite. But quit lit is not merely the frustrated cries of those who have lost the game; it is a jeremiad against the darkening of the infinite where it should be – it must be – shining the brightest.

The advancement of neo-liberal corporatism which is shaping our politics and our universities is the triumph of the finite game. The obligations of each generation to strive for justice, to protect the planet, to help the less fortunate, and to forge new horizons of knowledge are being replaced by the ethos of a financial ledger. We are all living the experiences of my academic generation as we watch the infinite dissolve before our eyes.

“Evil is the termination of infinite play”

We are trapped in a unique period of history as the promise of infinite horizons decays into malevolent victories won by the most small-minded amongst us. But from the prowl of the finite emerges the possibility of rebirth and revolution.

We are a generation whose lives span the chasm between the memory and promise of the infinite of Kennedy and Obama, and the current triumph of the finite. Disillusioned by the rift between the expected permanence of the infinite and the reality of its decline, we are the generation that must resist the ongoing normalization of the finite and we must counter the claim that a society based on the infinite is an illusion. It is vital that we reclaim our universities, and the endless expedition of education, from the snarl of the finite game and reinstate them as bastions of the infinite. We must rescue our politics from the forces of corporatism and hierarchy and we must demand that our government and institutions of higher learning play a new game. One in which we all win.

–RWG–

(Quotes are from Carse’s Finite and Infinite Games)

Richard W Goldin, Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com