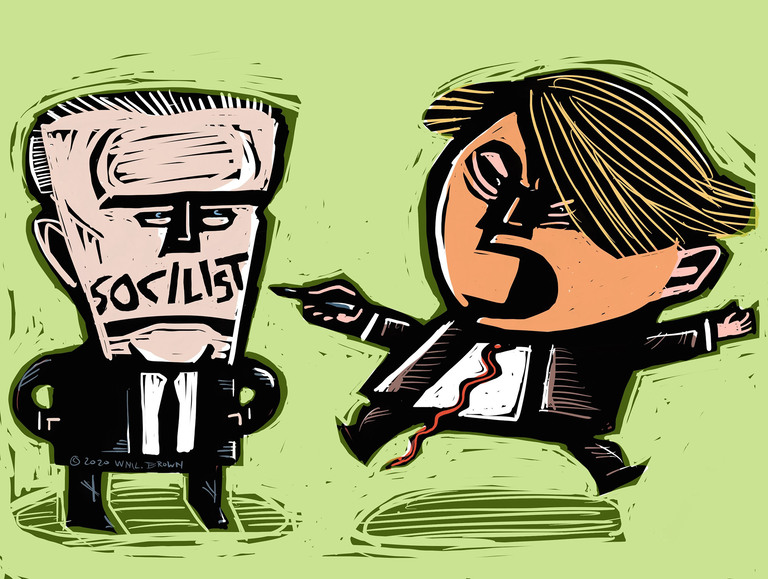

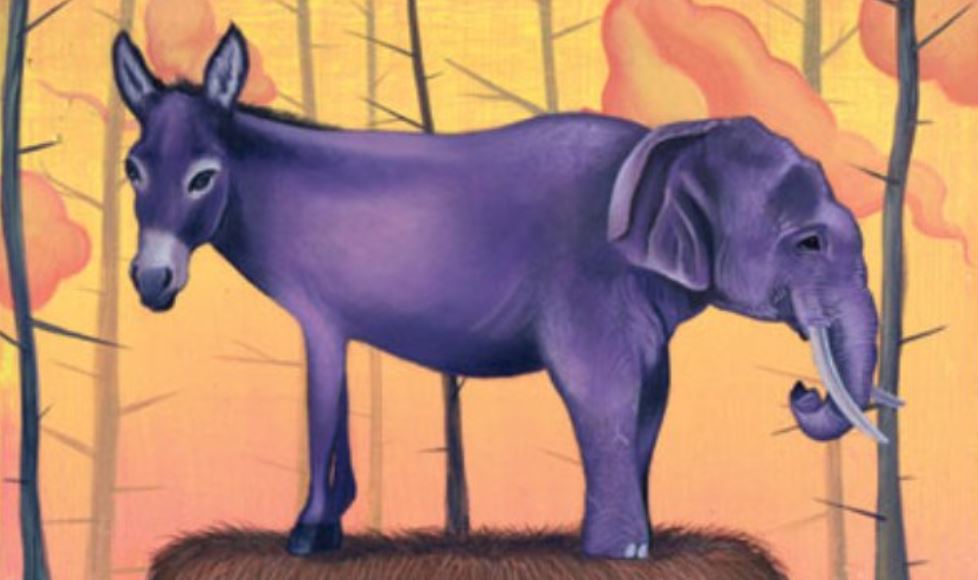

Democrats and Republicans are engaged in a con game in which each party expresses horror at the other’s supposed undermining of “American values.” The resulting fear and anger generated by these performances of opposition are meant to divert attention from the single, shared philosophy which underlies both parties.

Democratic and Republican politicians believe that the wealthy and the powerful – the corporations, the CEOs, the banks and Wall Street, and the politicians themselves – are America. The rest of us are viewed as replaceable cogs. This delusion of aristocracy (rule of the “better”) obscures the brutal reality of oligarchy (rule of the wealthy) which structures both parties.

The Republicans and the Democrats will never change the political and economic structures which have resulted in economic inequality. They have, together, assiduously built those structures over the years, disguising their complicity with simulations of difference and performances of disagreement.

The 1% controls the 99% not through force or oppression, but by creating a falsity of choice. This requires that significant political change must always appear to be within the grasp of voters even though nothing ever fundamentally changes.

It is optimistic to think that the political parties are corrupted by the wealthy. Claims of corruption give the illusion that the politicians and the wealthy are actually separate entities, with money being the tie that binds. But politicians aren’t corrupted by the 1%, they are part of it. The parties function as the political arm of the powerful. Even if politicians are not part of the 1% in terms of wealth, they share the same devotion to wealth accumulation and a patronizing disdain for the non-wealthy.

Voters have been constructed to believe there are differing fundamental principles distinguishing the two parties. But the dissimilarities are merely political strategies designed to give the appearance of difference and the illusion of choice. Principles are fundamental and enduring; strategies are malleable and contextual.The conflicting strategies are not goals in themselves but function to obscure the singular, shared principle of economic inequality.

The wealthy and powerful don’t want resolutions to social and cultural battles; they use the differing strategies to promote, continue, and often exacerbate, these fights as elements of distraction. They don’t care which side of the duopoly is in power. Both parties serve the same function – continuing to drain the 99% of wealth for the continued benefit of the few.

Neither of the parties actually cares about the horrors from which they are pretending to protect their constituents, nor do they believe that these horrors would ever take place. By protecting their followers from non-existent threats, each party can then claim to have saved this country from something that was never going to happen.

The border wall was never a substantive policy; it was a diversion useful to both parties. The political Right could claim they were protecting the country from the lowly hordes and the Left could cry out against the degradation of these people. In actuality, Biden has continued many of Trump’s immigration policies and the wall can be climbed in six seconds.

But the wall was a useful strategy – it reinforced the pretense of differentiation through the trope of horror/protection while distracting voters from bipartisan policies supporting greater wealth accumulation and continued economic inequality.

The Republicans cried out that the Democrats were going to defund the police and the Democrats countered that only they would save people of color from police brutality. A great deal of energy and anger was generated, as was a large amount of fund-raising, as each party exhorted their faithful to support the different sides of this crucial battle. Then the Democrats took a photo of their elders kneeling, draped in Kente cloth, and that was pretty much it.

Democrats exhort their followers around the issue of voting rights, claiming they are saving democracy from the tyrannical Republicans. But Democrats have tried to kick third party candidates off ballots, they’ve promoted a bill which makes it more difficult for third party presidential candidates to obtain funding, and they have gone to court to win the right for party leaders to ignore the results of their own primaries. The goal is to promote a seeming opposition to Republicans through a disagreement over voting access while simultaneously limiting voters’ available choices to the status quo favored by both parties.

If both parties explicitly declared they were going to limit future presidential choices to only the two existing parties, and that party leaders could ultimately choose the nominees, there would be an outcry from those on the Left. Instead, both parties benefit from the illusion that the Democrats are truly fighting for the rights and freedoms of all voters regardless of their political affiliations or viewpoints. Political energy on behalf of giving more power to the people is diverted into the con game and a strengthened oligarchical duopoly is disguised as a battle for democracy.

It is not possible to bring about actual change, or any significant alteration of economic hierarchies, by supporting either party in the con game. The oppositional duality is an illusion; there is only one side – the philosophy of wealth. The appearance of opposition is a strategic performance which structures the game and choosing sides within it simply allows the game to continue. As the supercomputer in the film WarGames finally figured out, “the only winning move is not to play.”

–RWG–

Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com