The current intensification of social and political hierarchies is fueled by a Republican ideology which celebrates the hoarding of resources by a few, and worships inequality as the 11th Commandment. Proposals such as taking food away from the elderly or health care from the sickest have faced charges not merely of injustice but of outright immorality.

But what about the Democrats? As a party, they offer programs and policies that make some peoples’ lives better in the short run. But at the same time they are unwilling to eradicate the economic structures which trap people into needing those programs in the first place. Democrats are proficient at hurling charges of immorality at Republicans; but should they face the same charges for their own (in)actions?

The latest Democratic promises are being sold under the slogan ‘A Better Deal.’ The Democratic Party is now explicit that its standards for a just society are highly relativistic. The deal doesn’t aim to bring about actual social or economic equality; its objective is just to be better than the other guys. This seems like a very low bar. The slogan speaks the language of a brighter future while simultaneously dimming any expectations for what that future will be.

“A Better Deal” points in two directions. It is an ostensibly sympathetic attempt to improve the lives of the most needy; while it ignores, and therefore reinforces, existing structures of inequality. There is no singular metaphysical principle which can judge the (im)morality of these combined actions. We’ll need a different way of approaching the question.

Consider the following analogy:

Imagine there exists a huge mansion which, despite its already enormous size, continues to grow exponentially. Dozens of rooms are added even as you watch; a steady stream of Italian hand-chiseled marble, enough wood to destroy a small forest, and gleaming golden toilets as far as the eye can see.

Surprisingly, there are only a few people partying in a handful of the mansion’s endless rooms. The vast majority of the building remains unused, even as it continuously doubles in size. Standing next to one of the many overly-laden tables in the lavish banquet hall are Republicans and Democrats; both on their phones talking to the same brokerage houses, all focused on increasing the same investment portfolios.

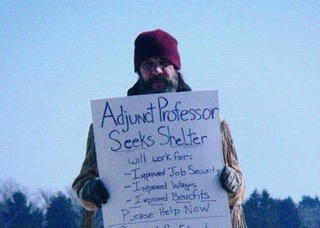

Down three flights of stairs, crammed into a small sub-basement room behind a well-bolted steel door, are all the rest of us. Those who work hard but receive the least. There is no way of leaving the basement other than through the steel door, and we spend most of our time blaming each other for our inability to break out.

The Republicans are certainly aware that we are down there. But they are the ones who pressed for the original basement excavation and the newly installed locks on the thickened steel door. They see nothing wrong with the situation and lack any ameliorative impulse.

Eventually, one of the Democrats – we’ll call her Demos – looks sadly at the door leading to the basement, experiencing a fleeting moment of guilt. Demos moves to the door, walking down the many stairs carrying a plate of her meager leftovers. Approaching the sub-basement, she loudly announces her arrival, proclaiming that food crumbs are now being shoved under the door. When someone cries out to her to open the door she glances quickly at the lock, and continues to feed the narrow slit between door and floor. Completing her task, Demos turns away, exclaiming over her shoulder “remember, if it wasn’t for me, you wouldn’t even have crumbs!” She runs back up the stairs, convinced she is a far superior person to those still attending the party she is so very eager to rejoin.

There are a number of factors involved in Demos’ actions. There is the overall upstairs/downstairs division, there is the refusal to break the lock, and there is the thrusting of food under the door. As strongly as some might believe that the immorality of the locked door is obvious – and thus Demos’ inactions are clearly immoral – it is difficult to apply a singular metaphysical certainty to her mixed responses. We want, instead, to stay within Demos’ own thought processes.

Demos demonstrates that the partitioning of people is wrong –

to her – when she carries her crumb-laden plate down the stairs in an attempt to ameliorate the situation. This “wrongness” does not necessarily bring with it a moral judgment on her part. Demos might feel that locking people in the basement is unjust, but does not rise to the level of immorality.

Demos pushes food under the door because she believes that the peoples’ deprivation is, at the very least, unfair. But when she is called upon to destroy the lock, she turns away from the door, and her convictions. This is where the question of immorality arises.

The Democrats do not deserve condemnation because they refuse to see our current economic and social inequality as necessitating an urgent moral response. Their failure lies in the contradictions between their belief in the wrongness– call it unfairness, call it an injustice – of our economic hierarchy, and their unwillingness to substantially transform it.

‘To sin by silence, when we should protest, makes cowards out of men.’

“Protest“ by Ella Wheeler Wilcox

Claims of moral “truths” are inherently subjective assessments. But one doesn’t need an external “truth” to question the morality of the Democrats. Their potential immorality is internal; it occurs the moment Demos refuses to alter the inequalities she regards as wrong.

Demos surmises that the situation is unfair, has the ability to fight it, but chooses perpetuation instead. Shoving food over the threshold, calling it “a better deal,” becomes the alternative to smashing down the door and freeing those trapped in the basement.

Republicans are convinced they are on a divine mission to expose an underbelly of “unworthies.” Their possible immorality is tied directly to the construction and advancement of inequalities. Democrats aim at ameliorating the effects of what they perceive to be Republican immorality; but they refuse to address the underlying causes.

For the trapped, there is little difference. We remain behind the bolted door, listening to floating bits of music from a party of Democrats and Republicans we will never be allowed to attend.

–RWG–