A massive mansion sits on ten acres of over-groomed lawn. An odd combination of faux classical Greek and Las Vegas-style Roman architecture, most of its too-many-to-count rooms have never been used.

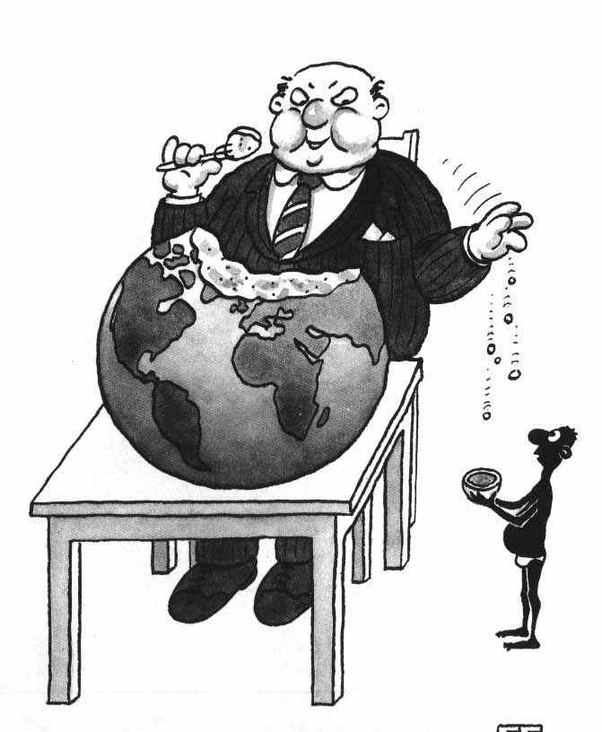

A lavish party is taking place in the Milton Friedman banquet room. Republican and Democratic party leaders enjoy a sumptuous feast encircled by the wealthy and well-connected. The leaders sit across a table laden with the kind of expensive, esoteric cuisine the rich pretend to like when they graze together. The Democrats and Republicans sit on different sides of the same table, enjoying the same food.

The non-wealthy are all locked in a small, cramped basement room. Small slivers of light and air enter intermittently from a row of slightly-opened windows near the ceiling.

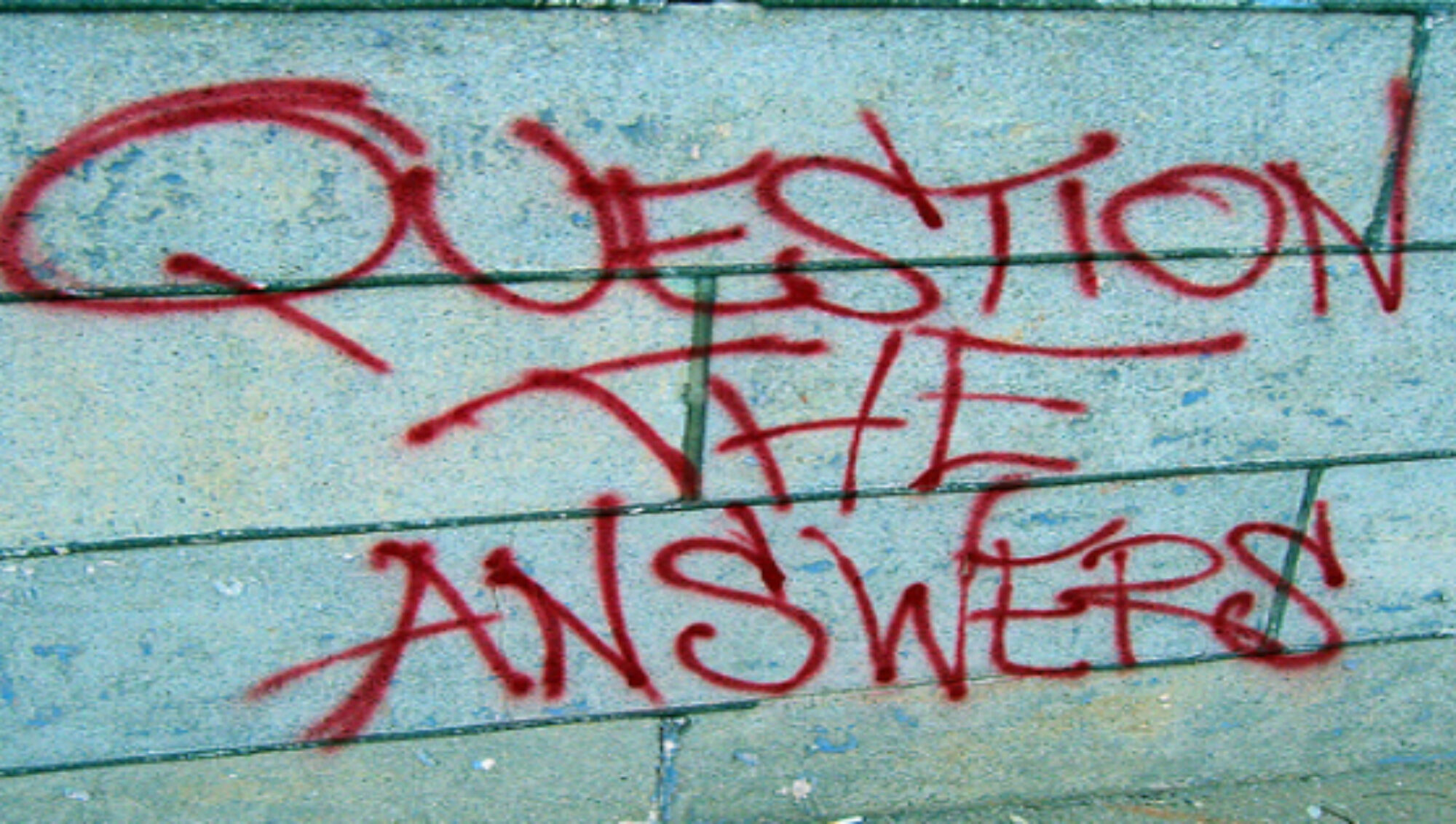

Every so often, a Republican appears at the basement door and eagerly installs a bigger, stronger lock. When some in the room shout “let us out!” the Republican replies, “I’m going to put locks on the windows.”

Occasionally, a Democrat wanders down to the basement, carrying a small plate of leftover crumbs. The Democrat pushes the crumbs under the door, whispering words of sympathy and sorrow.

When the people cry out – “remove the lock, let us out of the basement!” the Democrat responds, “Oh, I don’t do that. But I do offer crumbs.” The Democrat trots up the stairs with the empty plate, convinced that a crumb-pusher is a far better person than a lock-builder. With one final glance back to make sure the door is still locked, the Democrat leaves the basement, proud of their journey into generosity and compassion.

In the basement, people fight over the little they are given. They separate themselves to different corners of the room, accusing each other of taking extra crumbs. Those who claim that the lock could be broken if everyone worked together are exiled to a tiny curtained-off area. People from all corners point to the veiled space and laugh derisively before returning to the battle.

As the sounds of endless fighting drift upstairs, the Republican and the Democrat smile across the table and prepare to tell each other how much they love the sautéed ladybug wings.

–RWG–

Richard W Goldin; Lecturer in Political Science; California State University; thegoldinrule@gmail.com